Pandemic Anniversary: Teachers Reflect on How the Pandemic Affected Their Profession

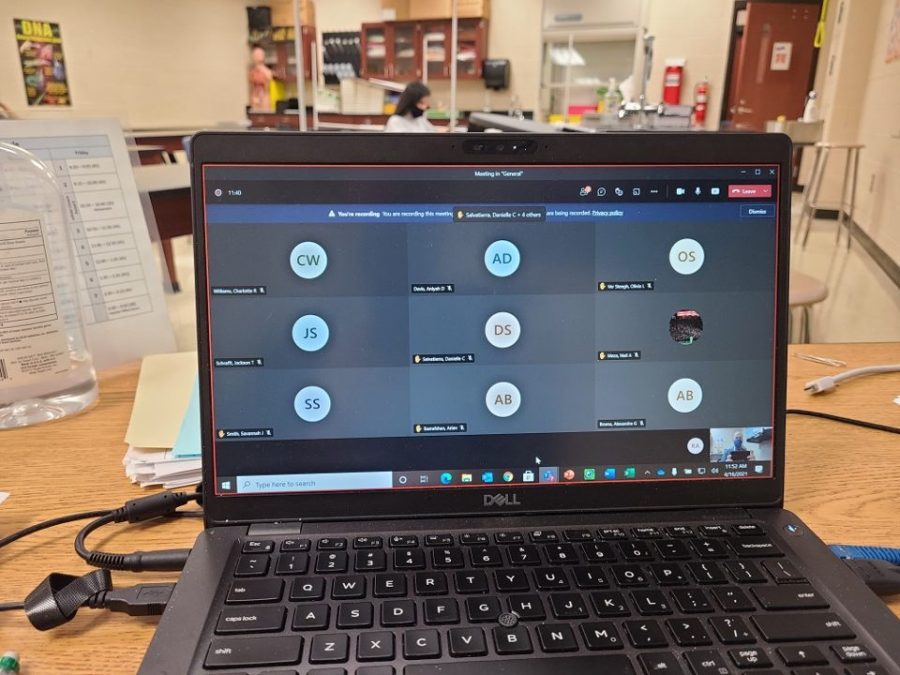

Chernick’s fourth period chemistry class, invisible wall and all. Bubbled initials stare back at him.

April 23, 2021

10 students sit in a cold, dull classroom at nine in the morning. Meanwhile, these students’ 20 classmates at home could be doing anything behind their screens: sleeping, scrolling through TikTok or playing Xbox.

Teachers wonder what the online portion of their class is doing during instruction. Are they working? Are they cheating? Are they drooling on their keyboards, asleep?

Students’ cameras are off, so teachers stare at a sea of initials, with a few profile pictures of memes here and there.

Due to COVID-19, teaching and learning aren’t how they used to be. With passing the one-year mark of the pandemic and nearing the end of the school year, teachers reflect on the obstacles of education given the circumstances.

Thomala Wright, who teaches Spanish, said the initials on her computer screen are like an “invisible wall.” A barrier, she said.

Wright came to Cambridge late in the 2019-2020 school year’s first semester after teaching in a foreign country.

“I did three years in Jordan, took a break, came back, and literally when I got back, after three months, that’s when COVID hit,” she said.

She described going online for the remainder of that fateful second semester as a “bomb,” and said she remembers thinking, “How is it going to be possible to connect with my students in ways that are really meaningful?”

She was unsure whether teaching during this time was something she wanted to do. She considered working for a non-profit or doing her doctoral work. Ultimately, after having a “head check and a heart check,” she decided to stay a teacher.

“With COVID, I have not felt successful as a teacher in the usual sense. I had to re-evaluate what success looks like,” she said in an email, after saying she is a “very goal-oriented” person.

Biology and chemistry teacher Mike Chernick had similar thoughts.

He planned to get his teaching certification in April 2020, but the test was pushed back twice until ultimately, he took it in December and passed.

Chernick was a long-term sub before a teacher, and when COVID-19 emerged, he had to leave the chemistry students he had already been teaching for 10 weeks at Cambridge. Another teacher took over the class.

“I knew them, and they knew me, and all of a sudden, I didn’t have them in my life everyday anymore,” he said.

Chernick has said teaching during the pandemic has “forced” him to get out of his comfort zone.

“My normal teaching style is walking back and forth across the classroom, very much animated, and I just can’t do that now,” Chernick said.

One thing that hasn’t changed? The reason he does his job, which he said is his love for students, he said.

Like Chernick, Carrie Bone, who teaches special education students, had trouble adapting her format of teaching to a virtual setting.

“I have lessons that if they get cut short, we move onto the next one. If it’s a great lesson and it goes over, we continue to talk about it. When you’re virtual, it’s stop and start,” she said.

The focus of her class is to teach vocational skills to her students, skills that will help them flourish outside of school.

She said, however, attempting to incorporate those skills online has been challenging.

“If we’re doing [hands-on work skills] at school, what is that person at home, that’s virtual, doing? That’s hard to recreate,” Bone said.

In the end, she had to figure out the answer to her question.

“We were having to switch to a lot of academics for kids — that wasn’t what their main focus was,” she said.

“I’ve really had to reach inside myself and be like, ‘what can I teach these students that they’re going to grasp and they can grow on, because our vocational opportunities are so limited?” Bone said.

In past years, her students have gotten opportunities to work in fast food restaurants, the Marriott hotel and different office companies. Now, they aren’t allowed to, but they still have the ability to go around the school, delivering mail and picking up recycling, amongst other activities. Nevertheless, the ability to do those during these times has been a challenge.

“People don’t really have mail because no one’s printing anything, or recycling,” said Bone.

She is worried for the future of her students and the class itself.

“My biggest fear is that COVID is going to get us in a position where it is going to be harder for our students to have opportunities outside the school buildings,” Bone said.

Despite the trials of being an educator during these times, the experience is memorable and something to grow from, said Wright.

“I think that my role as a teacher in the time of a pandemic is something that is history in the making,” she said.