“A Hunger to Create”: A Spotlight on the School’s Visual Arts Teachers

The creations of these fellow art teachers are coming "out of frame" and into the limelight for all to witness.

November 29, 2018

The school’s art program is run by three highly-trained individuals who put their all on the table every day to educate their students on culture, different forms of art and composure of art.

What students may not know is that all three of the visual arts teachers hold art careers outside of the walls of the school.

They may not know of David Batterman’s detailed collages or Samantha Harris’ history on agriculturally based work. They may not know the meaning behind Natalie Hudson’s pieces and the story they hold.

But soon they will learn of the history behind their teachers’ art and the backstories of their pieces.

Ceramics, Sculpture and Jewelry Teacher Samantha Harris

Living in Georgia all of her life, art teacher Samantha Harris’ environments have ranged from urban to rural, all the way to the town she works in today.

She said that growing up she lived in a town where people either wanted to be a mechanic or go to technical school. So she went to Southern Poly Tech — now part of Kennesaw State University — for architecture and engineering.

“I realized after a couple of years, I hated it,” said Harris.

“I was never computer savvy and outside of drawing architecture, you were spending a lot of time behind a desk,” said Harris. “And that just wasn’t what I wanted with my life.”

The University of West Georgia was then Harris’s new university with her major being art education.

Immediately, she dove into level one courses and foundational lessons, learning everything she could about art.

After graduating from West Georgia, Harris started to work in an elementary school in southern Fulton County.

“I was like, “Yes this is where I’m supposed to be,” she said.

Harris is currently on a break from making art for the public and is focusing on making mainly sculpture-based work in her free time.

Harris said that most of her works revolve and center around the depths of agriculture and farming in her childhood.

“And a lot of my artwork had to do with farming. West Georgia’s in Carrollton so it’s very rural. I really got into [the topics of] genetically modified organisms, factory farming, consumerism and the life of a living organism,” she said.

Harris said she’d love to see more collaborative classes, like combining two or more subjects to teach a career path that Cambridge may have not seen before.

“I would love to collaborate. I would love to collaborate with Mr. Thompson for engineering and welding, or work with set design for the performance arts, because we’re all essentially a family, we take and borrow from each other,” she said.

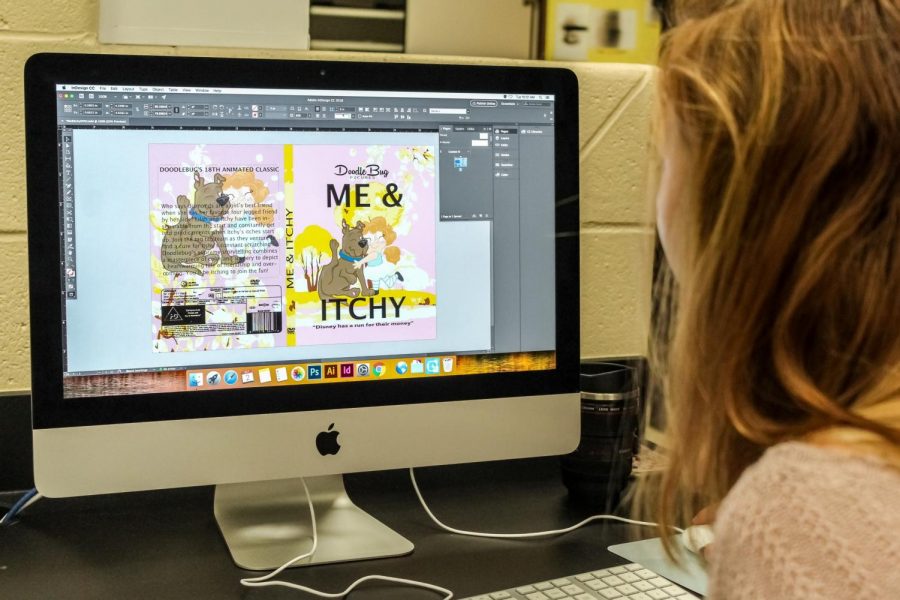

Photography and Graphic Design Teacher David Batterman

Walking into art teacher David Batterman’s room, you’ll see about 30 things upon stepping through the door: brand-new Mac computers, old Dell computers, an entrance to the darkroom, cardboard boxes with duct-tape surrounding them and more.

These things may not mean much to anyone else who walks into the room. But to Batterman, artistic inspiration may await these things in the form of his collages.

The art educator spoke about his collages, which debuted on his website in 2013.

These collages consist of characters with heads represented by carburetors, tank engines and oil tanks.

The inspiration for these pieces comes from mid-20th-century imagery in old magazines and other sources.

“All those things have a tendency to reduce to machines. Machines of consumption or machines of whatever they want you to do,” said Batterman.

However, after making a few of the collages with the automotive-human hybrids, Batterman started to branch out to create other pieces.

Russian items started to make an appearance in his artwork. In one piece featured on his site, Batterman superimposes his own characters over a black and white NASA map of a planned missile site.

“It’s the idea of not only militarism in everyday life, but also how consumerist society and the way that advertising, marketing, and militarism, prey on this base reactionary instinct,” said Batterman of the imagery.

Batterman said that with an artist, there is always intent with one’s work; it never comes out of a random occurrence.

“It’s about the thinking process that’s involved with it [art education]. It’s about having a problem and having a multiplicity of approaches to come at that problem and solve it in a unique way.”

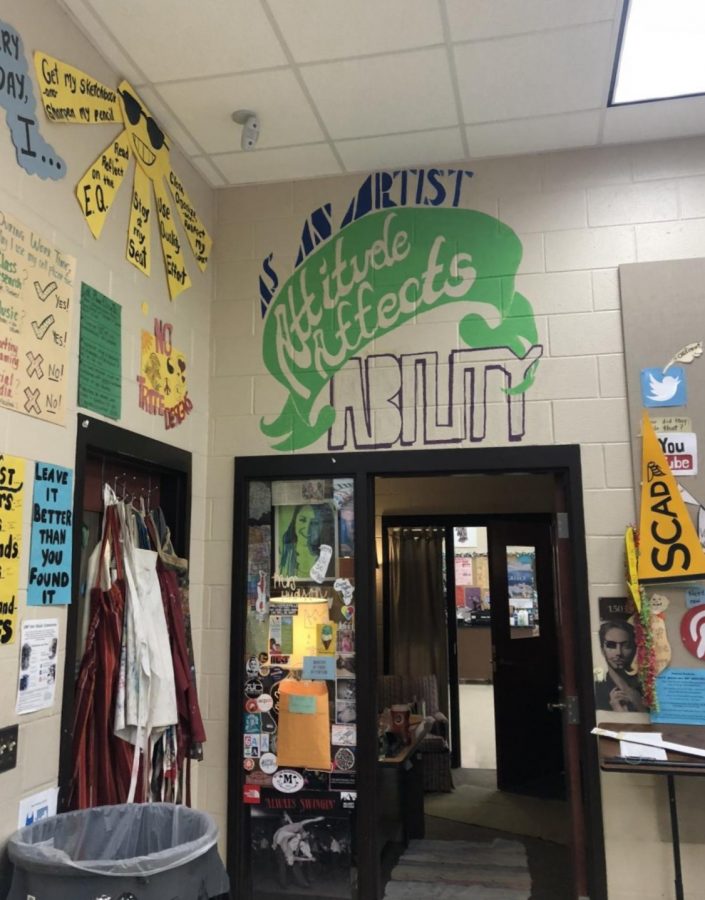

AP Art Teacher Natalie Hudson

This is a photograph of the mural that sits top of the door to the joint offices of Harris and Hudson.

Art Department Chair Natalie Hudson’s room is what an art studio in a movie might look like.

The room is decked out with a multitude of supplies littering the tables and paintings on the walls. Canvases and easels are scattered everywhere, and the brushes lie across the table like fallen leaves.

Hudson said she never expected to work in education.

In her young-adult life, Hudson didn’t know what she would want to do. Her aunt, with whom she was very close, proposed the idea of her getting involved with art education.

At her aunt’s suggestion, she decided to apply to Ohio State to major in art education.

However, after becoming a teacher, Hudson said she realized she was not getting enough practice at producing art herself, so she decided to pursue a master’s in art education from Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD).

“I felt that I had this hunger to keep making things,” she said.

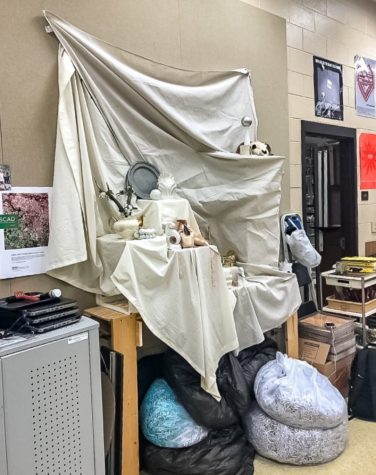

A drawing setup found inside of Hudson’s classroom.

Family conflicts Hudson faced growing up inspired her to create a piece for her master’s thesis. The piece represented the breakdowns in her family throughout her life and her perceptions of them.

The step-by-step ritual Hudson followed to create the piece was lengthy and took extreme patience.

Hudson said the piece was almost a performance piece, but intertwined with printmaking and visual arts, as well.

She would put out ornaments on a clean cement plate over which the audience would walk. As audience members crushed the ornaments, they would leave scratches on the plate.

Each time she exhibited the piece, Hudson would wait for all the ornaments to be broken before making a print of the plate. Over time, the viewer could see the plate deteriorate, and eventually, the viewer would see that the plate is on the verge of being destroyed.

“Every time I’ve set up this piece, it almost seemed like a social experiment,” said Hudson. “And you can always see someone look over their shoulder like they may stomp on it if they see it at all. It’s fascinating for me, which may say something about my psyche.”

Once Hudson graduated from SCAD with her master’s degree, she worked at Northwestern Middle School for a short time and later joined the school.

“I tell my students all the time, I’ve died and gone to art-teacher heaven,” Hudson said of her current job.

“It’s amazing, and the students are incredible,” said Hudson. “And it makes me feel shameful that I don’t have to deal with some of the complex things that my friends at other schools have to deal with.”