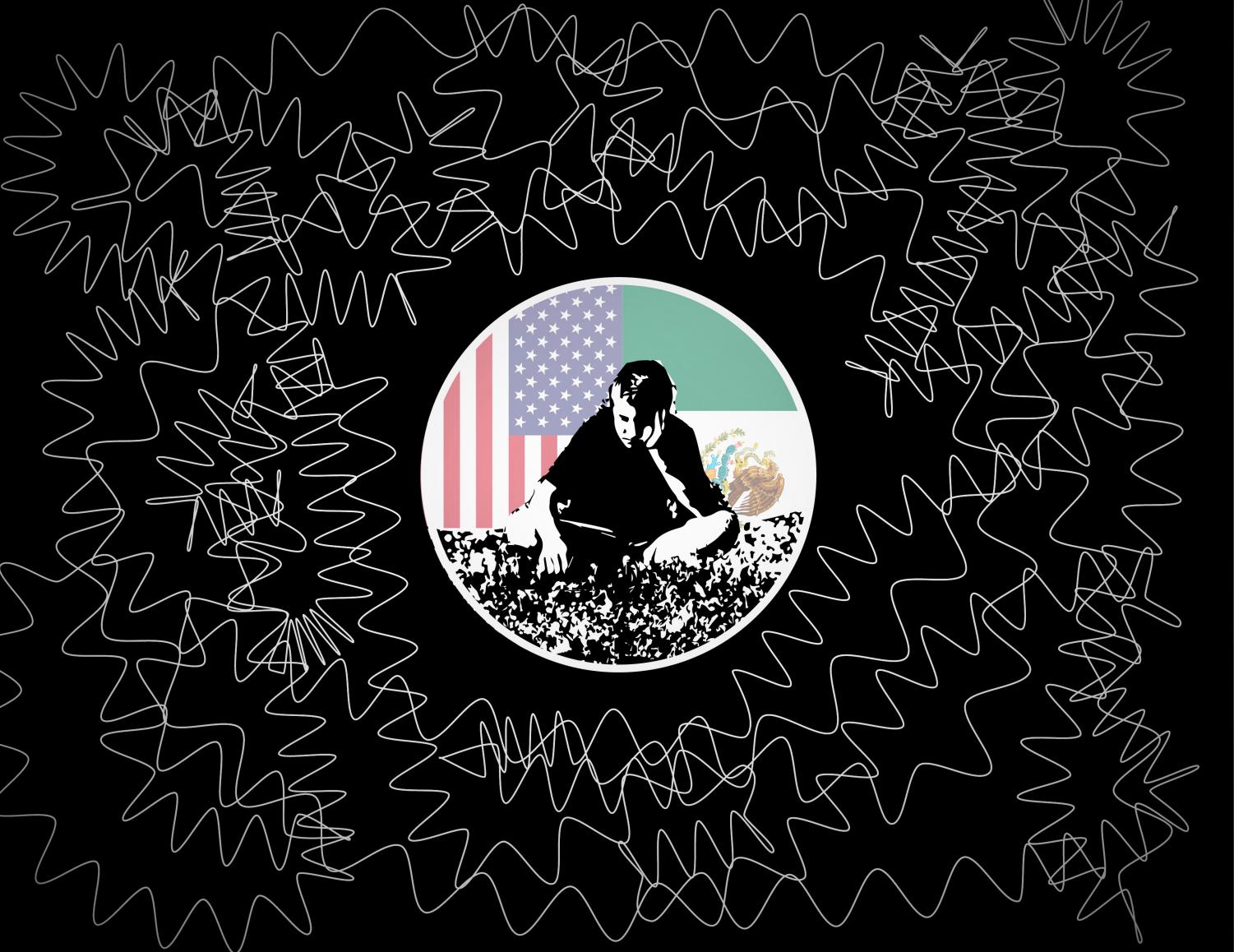

A Dreamer’s Tribulations: The Effects of DACA on One of Our Own

May 18, 2018

Since Daniel was three years old, the United States has been his home.

It’s where he’s gone to school, gotten his first license, worked his first job. It’s where he dreams of attending college and of one day becoming a sports representative for Nike.

He owes these opportunities to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, otherwise known as DACA, an executive order signed by former President Barack Obama in 2012.

Being a DACA recipient allows immigrants like Daniel, who were brought to the US illegally under the age of 16, to avoid deportation and enjoy certain privileges, such as getting a job and enrolling in college.

However, all of Daniel’s opportunities and aspirations could disappear.

President Donald J. Trump decided to rescind DACA last year, and though the program has not officially disappeared, it still hangs on a thin tightrope of court cases and Congressional debate. It is still unknown what fate lies ahead for immigrants like Daniel, known popularly as “dreamers.”

For Daniel, who was born in Mexico, and many other DACA recipients, immigration status is something they often wish to keep secret. Daniel is a pseudonym The Bear Witness is using in place of his real name.

Daniel said he read on Twitter last year that President Trump was planning to end the DACA program, but the official news was still a shock.

“At that moment, it’s just, like, it’s heartbreaking a little bit,” he said. “You feel like the opportunity has kind of been taken away from you.”

If DACA disappears, young immigrants like Daniel will no longer be protected from deportation.

For most teenagers, mistakes are a part of life, but for Daniel, any run-in with the law, even a misdemeanor, could jeopardize his entire future because of his status as a DACA recipient.

“In a way, it is kinda like, you know, the US is meant to be the state of freedom,” he said. “Me, I’ve been here my whole life, and I have a clean record.”

Even before DACA was in danger of being rescinded, the limitations it put on him left him feeling restricted.

DACA recipients cannot receive federal financial aid, travel outside the United States for extended periods of time or obtain a driver’s license in certain states.

“It kinda does frustrate me, like I’m capable of doing so much more with myself if I had the opportunities others do, but I just have to do with what I have and pray that it works out,” he said.

Daniel’s Journey: The Beginning

He was only three years old when his family decided to make the long journey to the United States. His little sister, who made the journey with them, was only six months old.

“I do at times remember a little bit of it,” he said. “It was a pretty long walk. I can remember that.”

“Sometimes there are helicopters that come by — back and forth — but other than that, you walk for a while. You walk. You walk. You walk.”

Daniel said many families come to the United States illegally because the legal route fails them.

“There hasn’t been really a way for Hispanics to come in and be a citizen the right way,” he said. “It takes a lot of time, it takes a lot of money and it’s so corrupt.”

According to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, immigrants are only eligible for a green card if they fit into one of a few categories, such as applicants with family members in the U.S. or who are sponsored by an employer.

And even belonging to one of these categories doesn’t guarantee someone will get a green card.

Daniel said his family moved because of the deteriorating conditions in his home country.

“We weren’t necessarily doing very well in Mexico,” Daniel said, “so my mom decided to move to the United States to just help us — my sister and I and herself — from that violence and the economic issues that we were having.”

Daniel said that despite the fact his Mexican heritage is embraced in his home, he and his siblings still feel very American.

“My sister speaks more English than she does speak Spanish,” he said.

Although he may remember parts of the long journey to the United States, at the time Daniel lived in his birth country was cut short by his parents’ decision to find him better opportunities.

“I’ve been here ever since,” he said.

The Second Move:

Although Daniel spent nearly all his childhood living in South Carolina with his family, in 2016 he made the move to Georgia to live with the family of a friend until he graduated from high school.

When Daniel was young, he always played sports against the family’s son back in South Carolina, and once that family moved to Georgia, Daniel made sure to stay in touch, texting and talking on the phone with the son.

One night, he and Daniel were talking about college, as they were both reaching the age where college was something they were starting to seriously think about.

“We talked about it, and he was just like ‘come stay with me for a year and a half until you’re eighteen so that, you know, you could take that dream of attending college and actually make it a reality,’” Daniel said.

This time, the move was a decision he made on his own after deciding it was necessary to fulfill his dream of attending college.

“Me going to college is very important because that’s what my parents want, but they don’t know how to get me there,” he said.

Daniel also said that the family’s son made it clear he would be expected to keep up his schoolwork while staying with them to ensure he had as many options as possible when it came time to apply.

“It just came across like ‘hey, this family’s super strict about studying, and education and stuff like that”, and they know the path to get there,” he said.

Daniel said the move has put him on the right path to reach his goal of attending college.

“Moving to Georgia with this host family has given me the opportunity of getting my grades up and having the opportunity of having options of schools to go to,” he said.

Daniel said the change in schools was a big adjustment, partly because Cambridge has a much smaller Hispanic student population than he was used to. He also said it frustrates him that many privileged students don’t take advantage of their circumstance.

“I wish I had their opportunities,” said Daniel.

Dreams for the Future:

Being a DACA recipient has allowed Daniel some of the same coming-of-age experiences as American-born teenagers, including getting a job reffing for younger kids on the weekends and getting his driver’s license.

However, when it comes to his dream of attending college, his options are limited.

DACA recipients cannot receive federal financial aid, and Daniel said many colleges also will no longer offer him scholarships in fear of paying for a student who may be in danger of deportation in a couple of months.

Despite these limitations, Daniel said he has no option but to stay positive.

“I’ve been here my whole life, in this situation,” he said. “If I try to point out the negatives, then I wouldn’t be in a good place.”

Nestled within his strength and optimism also lies a vision of what he hopes might emerge as his “perfect DACA,” a program that would allow recipients who have clean backgrounds a pathway to citizenship.

However, Daniel remains confident things will sort themselves out one way or another, even if DACA doesn’t survive.

“That won’t change my perspective on keeping it positive,” said Daniel. “Because that’s how pretty much I was raised.”

The Worst Case Scenario:

If DACA disappears, the consequences would be life changing for the hundreds of thousands of people in the program.

“Everything they have held onto for so long will all be gone,” said Bilingual Community Liaison Kathy Ouellete, who serves as a translator and personal connection between the school and families with a different first language.

Daniel said if he has to return to Mexico, every aspect of his life would change, from the home and job stability his family enjoys, to his dreams of studying business or marketing in college.

The end of DACA would leave most childhood arrivals, like Daniel, few or no legal options for staying in the United States legally.

Local immigration attorney Gustavo Aleman said the pressure to find a legal way to stay in the country sometimes leads DACA recipients into rash decisions.

“I know many kids that married their high school sweetheart at 18, 19,” Aleman said.

Although marriage may be a viable option for some, it isn’t for a vast majority of DACA recipients. There seems to be no legal option that would provide aid to a large portion of people within the program.

“Unless they qualify for some other form of relief, there’s not really a way to protect them,” said Aleman. “DACA is the protection.”

School social worker Stephanie Schuette said although there is no official record of Cambridge students who are DACA recipients, Daniel isn’t the only kid in the community who is affected.

“I did hear from a couple of kids that were comfortable voicing,” she said. “They were really worried.”

Schuette also said many DACA recipients were especially scared because of how unfamiliar they are with the countries they came from.

“That’s not their country,” she said. “That’s their heritage.”

For Daniel at least, giving up on hope is not an option.

He said regardless of the fate of DACA, he and his family believe things will work themselves out, which is why they don’t have a contingency plan.

“We’re just kind of going with, you know, hopefully, it all works out,” he said, “and if it doesn’t, then we just keep going until something else happens.”