Day 3: Anxiety Series

DAY 3

May 22, 2017

Dear Readers,

As the editors and I were mulling over what to write about for this series, the topic that consistently came up was academic anxiety.

We all had stories of friends who timed when they could cry during the day, and friends that stayed up until 4:00 in the morning to finish homework. We all knew how bad the anxiety was when it came to doing well in school and getting into college.

We saw it all first hand as many of you have.

So we decided to write about it in a three-day series that explores the questions surrounding where anxiety starts and how students deal with it, specifically here, at Cambridge High School.

Our reporting has led us to issues such as AP classes, college admission requirements and the emotional effects of anxiety.

With these stories, we hope to promote awareness of an overwhelmingly large issue and give hope for a brighter future.

Thank you,

Halle Larson

Editor-in-Chief

Part 8: The School

Call it pressure. Call it stress. Call it anxiety.

Call it what you want, but the dark circles under your eyes and the headache pushing against the back of your skull are commonplace in schools across the country, where kids feel pressure to excel academically.

But where does this pressure originate inside Cambridge?

Counselor Jennifer Sidelinger said she believes students deal with a great amount of pressure that is, in actuality, mostly coming from themselves and their peers. She said that, rather than enjoy their teenage years, most students spend their entire high school career focusing on one thing: college.

Sidelinger said that while she does not believe parents force their kids to do things they wouldn’t want to do, she thinks parents do rightfully have a role in their children’s academic lives and should be pushing their kids, to an extent, to succeed academically.

There are high expectations, she said, and students want to live up to those expectations, promoting stress and anxiety.

For this article, The Bear Witness spoke to 26 random students in the school cafeteria about their levels of academic anxiety. Students were asked to rate their anxiety on a scale of one to 10 and to explain which factors contributed to their stress. Every one of the students interviewed said his or her stress level has been at a five or higher at some point in the year.

During these interviews, most students complained that teachers seemed not to consider other classes or extracurricular commitments, such as sports or jobs.

Freshman Abi Beirne, one of the 26 students, said teachers “absolutely do not” take into account anything outside of their own classrooms.

“It prevents me from enjoying things,” said Beirne.

Junior Marryam Khan, who takes four AP courses, in addition to other honors-level courses, agreed with Beirne. Exhaustion, lack of concentration and an unhealthy diet are just some of the symptoms of school stress and anxiety, she said.

Humanities Director Sara Faircloth said that working around other classes is difficult, adding that she tries to keep her students’ best interests in mind.

“It’s difficult to plan around other classes since my students have such varied schedules and teachers, but I try to provide as much flexibility as possible with deadlines,” said Faircloth.

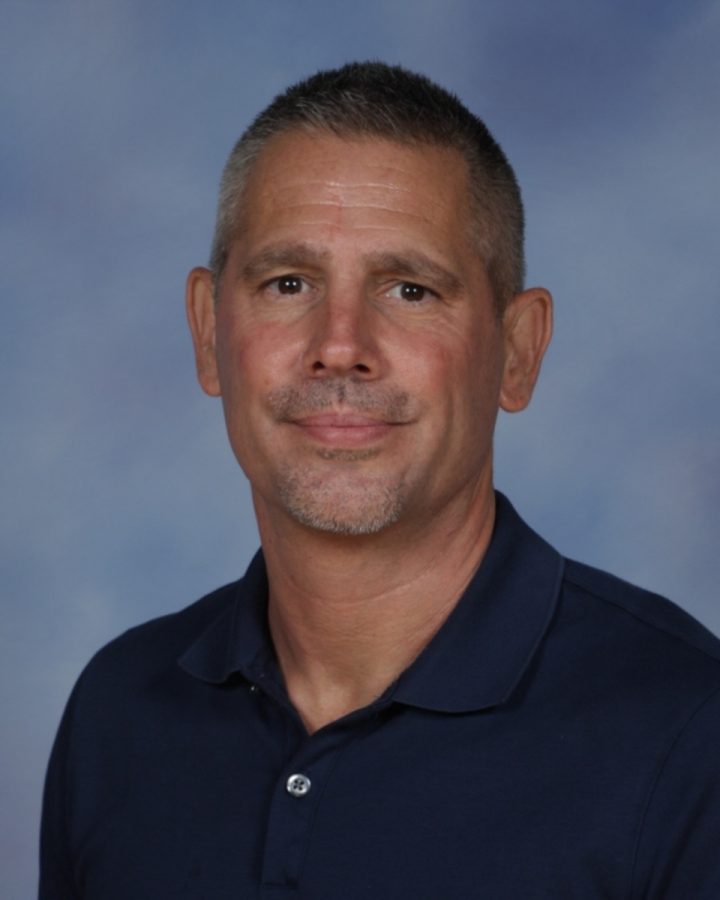

James Campbell, who teaches AP US Government and AP Comparative Government and Civics echoed Faircloth’s views.

“If a majority of students already have two tests or major assessments on some day, I will make sure I put my quiz or test on another day. If only one student is in that situation, I am usually willing to accommodate that student by allowing him or her to take my assessment early or late,” said Campbell.

AP Calculus teacher David Pomerance has a different view on the matter. He said the schedules teachers make for their courses are often too complex to work around other classes, without sacrificing their own curriculum.

“Instead, I am mindful to assign work in a time frame that makes it possible for students to pace themselves. If they have to spend more than 30 minutes per day on my class to be successful, then there is an issue to investigate,” said Pomerance.

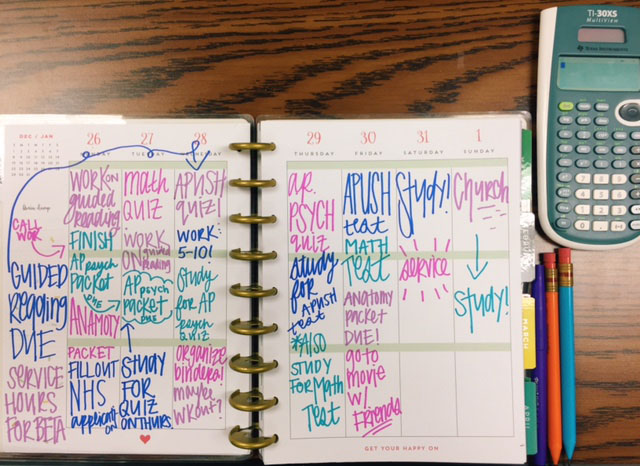

Junior Ava Stone said her stress comes from applying for colleges and rigorous AP and honors courses. With three AP courses, Stone is stressed enough as it is, she said. However, she juggles a job on top of her school work, resulting in a lack of sleep, which sometimes affects her academic performance.

Sidelinger urges students not to “beat themselves up so much” and remember things like failing a test or having a B in a class, instead of an A, is not the end of the world. Acknowledging that school workload and pressures from teachers, parents and fellow classmates can be overcome is the first step to maintaining a healthy, happy life, she said.

“That is what I want students to know. That, you know, you hit a bump in the road, or you’re not the salutatorian, or whatever, it’s okay. You can still get where you want to go,” said Sidelinger.

Guest Columnist: Brian Wallace, Economics Teacher

“What college are you going to?” “How many AP classes have you taken?” “What’s your class rank?” “Have you completed your Beta hours?” Did you get into National Honors Society?” “Did you get Hope?” “What’s your safety school?” “How many clubs or sports have you participated in?” “How many cords do you have for graduation?”

These are questions I hear every day in my class and in the halls, (and sometimes at Starbucks in the middle of the day as the weather gets warmer), from students who are trying to measure themselves and each other against the giant scoreboard that high school has become.

I have watched students cry because their class rank was 7 rather than 4. I have heard students whisper to each other “How did SHE get into (insert Ivy league school here)?”

I have witnessed frantic club-joining as students try to pad their college resumes.

I have seen students enroll in AP classes, in which, they have no interest in an effort to bolster their academic transcripts.

I have seen kids crumble under the pressure of academic and extracurricular demands that no teenager should be asked to take on.

I have received desperate e-mails from parents and students who are terrified that every B or C puts the future of college, graduate school, and a successful career in jeopardy.

I’ve watched our school fill a room with pillows and carpet to accommodate students who simply can’t deal with the pressure, and bring puppies to the media center during exam week to help students combat their unmanageable anxiety.

How did this all happen? When did the focus of high school shift from learning to performance; from peer socialization to peer competition; from feeling that your life was filled with limitless possibilities to feeling like you can’t possibly keep up?

The answers to these questions could fill volumes and are likely some jumble of the following: social media, The College Board, rising tuition, parent expectations, out-of-touch teachers, graduation yard signs, standardized testing, Zell Miller, 7 points for honors and AP classes, hours of homework, cords and medals, # of letters in your Senior Post, and “13 Reasons Why.”

The problem with that list is that it’s incomplete. And that’s a problem because I probably left off 100 things that weigh on our students’ minds every day. And that means that it’s not a problem with an easy solution.

It’s tempting as a teacher to say things like “take deep breaths” or “your life doesn’t depend on what college you go to,” but when you watch kids have actual panic attacks over whether a quiz might drop them from a 93 to a 92, you realize these platitudes are insufficient.

As parents and teachers who have the benefit of perspective and can look back on the arc of our lives, we know, (or should know), that high school rarely makes us or breaks us, but when a community perpetuates a flawed perception as a reality then all the pep talks in the world can’t make anyone feel better.

Ultimately, the only reassurance might be time and the ability to look into the past with clarity. The only comfort might lie 20 years in the future when you hold your children, go to your job in the morning, come home to your spouse, make your mortgage payment and realize your life seems to work, despite the fact that you got wait-listed at Vanderbilt, earned a C in AP Biology or were ranked outside the top 25 percent of your class.

And while I believe that the vast majority of our students will find their way just like their teachers and their parents did, I worry that their confidence is being eroded and their self-esteem is being damaged at a critical time in their lives.

I worry that as teachers, parents and peers feed this cauldron of pressure and expectations, we are sacrificing the joy and carefree nature of youth in the name of SAT scores and college banners.

I hope I’m wrong.

Perhaps these things are the new high school rites of passage in the way that worrying about your prom date, and whether you were going to college or getting a job after graduation was for students 40 years ago.

Perhaps, but each year, as I watch the parade of students file into the Student Center for their class rank and witness the tears, or slumped shoulders, or gasps of relief, or faces filled with despair, I wonder what went wrong and if there might be a way to recover the emotional and academic balance that seems, for many, to have been lost.

Part 3: It’s Your Choice

You ever find yourself cursing at the raining sky, with an AP exam prep book clenched in one hand and a half-empty Starbucks coffee in the other, pen ink staining your fingers red, because you’ve been furiously correcting your own work for classes you only took by the demand of the great Gods?

No? Oh.

Well then, maybe you’ll relate more to this scenario: It’s late. And not like, “Oh the sun’s gone down late.” More like, “If I fall asleep right at this exact moment I can get two hours and 27 minutes of sleep” late. You’ve got essays due, projects to start and homework to rush through.

Why is this happening? Maybe, you think, it’s because of the number of APs you’re taking. So why did you take so many?

You run through the suspects: parental pressure, counselors, peers trying to one-up you, college.

Sure, blame all that, but it’s your fault.

In the end, more often than not, you are to blame for your own academic stresses. Yes, a classroom and its teacher can be stressful, but it was you who decided to take that class.

A student may feel threatened or undermined by the rigor of classes that other people are taking, but you don’t have to take those classes to be on par with other students intellectually.

You should do something in hopes of finding fulfilling success, not in hopes of finding the approval of others.

So let’s go through it all and start with parents pressuring you to take these classes. You aren’t your parents. You aren’t your mother or father, and you’re not your sibling who achieved in different areas.

No, I’m not talking to students whose parents literally fill in their schedules for the year without their consent.

I’m talking to the students who feel like they have to prove something to people by taking classes they hate. Why not take enjoyable ones that they see a future instead?

Don’t take AP Literature just because you feel like you need to keep up with your peers. You think you’re competing with them for colleges? That may be true, but colleges look for more than just nine APs.

Here’s some advice from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s admissions Q&A site: “Challenge yourself in a way that is reasonable for you, while making sure that your course load provides you with material that keeps you excited and engaged, and that you have balance in your life. What we are saying is that, despite what you may have heard, college admissions isn’t a game of whoever has the most APs, wins.”

Now, I’m not bashing APs. They’re a great source of intense learning. But the point of APs isn’t for you to be memorizing facts for the next test or stressing out because you hate the course.

APs are supposed to challenge you on topics you’re already interested in and want to pursue. If you’re interested in AP Calculus, AP Literature and AP Music Theory, then go ahead and do it.

This delves into another point of pressure you may place your blame: college admissions. But allow me to preface this with a quote from Denise Pope, a senior lecturer at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education.

“Colleges don’t always accept the courses for college credit, many students end up repeating the course in college anyway, and you can run the risk of memorizing material for a test versus delving into a subject and exploring it in an enriching way,” Pope told Stanford News in 2013.

You shouldn’t build your life around a single college or university. You should build your life by challenging yourself where you seek challenges. If you do that, you’ll most likely end up at the college right for you.

“You will likely find that success in life has less to do with the choice of college than with the experiences and opportunities encountered while in college, coupled with personal qualities and traits,” writes NPR.

A success story doesn’t start because you went to Georgia Tech, Kennesaw State or Georgia Southern. The success story starts with what you did with your time. That’s the same in high school. It doesn’t matter that you’ve taken 12 APs.

What matters is that you challenged yourself to succeed in what interests you.

The choice is yours and yours alone. You shouldn’t hurt yourself by taking on the psychological torture of classes that give you no joy. Your future is defined by you, not by the colleges you get into, not by what your parents want, not by your counselors and not by your peers.

At least, it shouldn’t be.