An Inside Look at Anxiety in Cambridge High School

DAY 1

May 17, 2017

Dear Readers,

As the editors and I were mulling over what to write about for this series, the topic that consistently came up was academic anxiety.

We all had stories of friends who timed when they could cry during the day, and friends that stayed up until 4:00 in the morning to finish homework. We all knew how bad the anxiety was when it came to doing well in school and getting into college.

We saw it all first hand as many of you have.

So we decided to write about it in a three-day series that explores the questions surrounding where anxiety starts and how students deal with it, specifically here, at Cambridge High School.

Our reporting has led us to issues such as AP classes, college admission requirements and the emotional effects of anxiety.

With these stories, we hope to promote awareness of an overwhelmingly large issue and give hope for a brighter future.

Thank you,

Halle Larson

Editor-in-Chief

Part 1: College

For many students, college is a constant, nagging thought in the back of their heads. Whether it manifests itself as long nights spent cramming for a test, mornings devoted to club meetings or schedules chock-full of AP courses, the pressure to be the best is ever-present.

Whether the stress is caused by the pressure to take rigorous courses, to do well on standardized tests or to pile on extracurriculars, college admission requirements, both real and perceived, can create anxiety for high school students.

“My SAT score is constantly in the back of my mind,” said junior Amelia Green.

Standardized tests are a major contributor to stress for juniors and seniors, several students said. Many upperclassmen will have taken at least one of these tests multiple times in hopes of bringing up their score.

While the school offers some SAT-prep classes, parents often pay for courses offered by private companies.

Daniel Audia, an admissions counselor at Kennesaw State University, said standardized tests are necessary to some degree.

“The GPA provides a larger sample of academic data when compared to a few hours of a standardized test. However, some high schools may be more difficult to succeed in when compared to others, so the SAT or ACT can provide a level playing field in some respects,” said Audia.

These tests aren’t the only daunting college admission factor that students have to face.

Green, who visited Harvard in October, said she met a student there who wrote 23 different application essays before feeling she had gotten it right.

While published admissions requirements are helpful guidelines in determining where you can, or can’t, get in, Katie Faussemagne, assistant director of undergraduate admissions and regional recruiter at Georgia Tech, said a one-size-fits-all approach to college admissions simply doesn’t apply.

“There is no formula. There is not one activity, class or test score that guarantees admission,” said Faussemagne.

Will Brown, associate director of regional recruitment at Georgia College and State University, seconded this point: “The biggest misconception about college admissions is that it’s all about numbers. Never underestimate the human element of the process.”

Yet, junior year is infamous for being the most challenging year of high school because many students feel the need to pile on AP courses and extracurriculars.

“This has probably been the most stressful year,” said junior Payton Lane.

“How in the world are we supposed to fit in 20 extracurriculars, seven AP’s and sleep?” said junior Alejandro Becerra, who is taking five AP classes this year. Becerra said he believes anyone aiming to get into an elite college must “renounce sleep and sanity.”

Junior Ellie McGowan said she also has felt the pressure to load up on rigorous classes.

“When I was a freshman, I really wanted to go to UGA, and I ended up taking a bunch of AP classes,” said McGowan. However, she said that taking so many rigorous courses have affected her GPA, a fact she now regrets.

McGowan still feels the pressure to meet certain college admission standards as a junior. She said she finds herself worrying constantly and asking, “What can I add to my life to get me into college?”

However, the stress isn’t limited to juniors. Many underclassmen find themselves worrying prematurely about what they need to do to get into the college of their dreams.

“College has always been on the radar,” said sophomore Vanessa Haak. “There’s a lot of pressure just in general to hit every course and do every extracurricular, even if it doesn’t mean anything to you personally.”

However, Faussemagne, of Georgia Tech, said this kind of pressure is unwarranted.

“Do not participate in an activity because you think it will look good on your application. Find something to do outside of the classroom that excites you, that you can lean into.”

Even so, there is no denying that highly competitive schools, such as Georgia Tech, have high expectations. According to the Georgia Tech admissions website, the school admitted 26 percent of applicants in 2016, which is less than half the acceptance rates of UGA (53%), Kennesaw State (53%), and Georgia State University (57%).

Among the students admitted to Tech in 2016, half scored between 30 and 34 on the ACT or between 1330 and 1490 on the SAT. And if that wasn’t enough, half of the incoming students took between seven and 13 AP or other college-credit courses.

Haak explained that, for students trying to enter these selective schools, even a single test can feel like a life or death situation.

“Oh, if you don’t get an A on this test, kiss Tech goodbye,” said Haak, describing how the pressure to get into college can distort a student’s thinking.

Even freshmen feel the pressure to start preparing for their future.

“You constantly have to worry about ‘should you take the accelerated program or on-level?’” said freshman Duaa Tariq.

Tariq also said students can feel pressure to take the same rigorous classes as their friends.

“When your friends also take a lot of hard classes, […] you try to get to that level,” she said.

Despite this pressure, Freshman Greg Elsey chose not to take AP classes this year.

“I didn’t want to deal with the stress,” said Elsey. “I just want to settle into high school.”

The college admissions process may serve a reasonable purpose, but it can add insurmountable stress to the lives of teenagers already struggling to find themselves, their interests and the people they want to be around.

Cambridge counselor Kellen Kuglar often finds herself advising students on how to stay sane and healthy when dealing with college admissions.

“I ask them to look holistically at what [they] really like to do at the end of the day and focus their energy on that,” said Kuglar.

Brown, of Georgia College and State University, encouraged students to keep a positive attitude, adding that one bad test grade or college rejection letter isn’t the end of the world.

“At the end of the day, be sure to smile, because no matter how stressful it may seem, it will all work out in the end.”

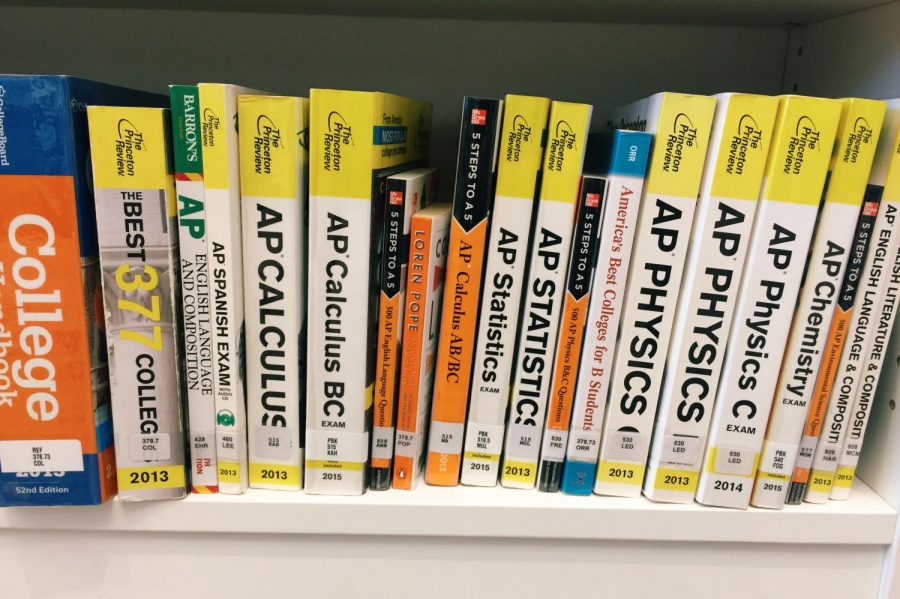

Part 2: AP Classes

In the 2000-2001 school year, 844,741 students took Advanced Placement (AP) exams according to The College Board, which runs the program.

By last school year, that number had more than tripled to 2,611,172.

The AP program was created in the 1950s to better educate the population, challenging driven students to work at the highest level they can and preparing them for college.

Mark Schuler, who graduated high school in 1984 and has been teaching AP history classes since 2005, said he didn’t even know what AP classes were when he was a student, as only a few high schools in his area offered them.

For most schools around the country today, however, “AP” is no foreign term.

Cambridge High School exemplifies the rise in APs, with 79 percent of students taking at least one AP course according to the school’s website.

Other schools nearby, such as Alpharetta High School (70 percent) and Milton High School (83 percent), have similarly high AP participation rates according to U.S. News.

However, schools farther away in Fulton County show lower AP participation percentages, including Chattahoochee High School (65 percent), Centennial High School (55 percent) and North Springs High School (58 percent).

The increase in the demand for AP courses has led some teachers to change what they do in the classroom.

English teacher Suzanne Wren, who taught AP Language for 10 years and has taught AP Literature for eight years, said she was able to do more and grade faster with smaller classes. In the past, her class might read 12 books in a year, but now they read eight or nine, she said.

“I miss smaller classes because I could reach students better; we were able to connect more,” said Wren. “It’s harder now, but you’re still gonna get the same depth and skill from my class. I’m gonna teach the way I teach, and I love teaching.”

Some teachers said that while AP curricula may not have changed, the students’ reasons for taking AP courses have.

A common motive is to have better chances of getting into college. The number of AP courses a student takes in high school has become a significant factor in the admission process at some schools.

“Before, students wanted to take AP classes for more rigor,” said Randy Gingrich, an AP English Language and Composition teacher for 16 years. “Now, students are taking them because schools are saying have X number of APs.”

That is one of the reasons sophomore Liz Willis plans to take 15 AP classes by the time she graduates.

She said she also takes them for increased rigor and, in the case of AP Psychology, for enjoyment.

“There is stress from my workload, but I can manage,” Willis said.

Sophomore Nishu Pawar said he believes the normal number of AP courses to take is closer to four or five, but he wants to take as many as 13. He said this is mostly for college, but also because harder work causes him to pay more attention and do better in his academics.

Another reason some students take AP classes is status.

Freshman Aarushi Malhotra is enrolled in all on-level classes.

“I do feel there is a judgment from AP class people to people who don’t take AP,” Malhotra said. “And I don’t think people should be judged or be judgmental by what classes they take, so I’ve hung onto that and not really given too much thought to it.”

Schuler said students want to distinguish themselves from others and take APs so they’re not in the “other classes.”

“I think it’s a tsunami,” said Schuler. “Once somebody takes it [AP], the neighbor wants to take it, and then another neighbor wants to, and then the whole subdivision is taking AP.”

Some teachers said this attitude shift regarding AP classes has a positive side, as it leads more students to challenge themselves and gives them more insight and knowledge.

However, the same teachers said they’ve seen many negatives from the change, including stress, anxiety and shame.

“I see stress and anxiety every day — some students more than others. The high-achievement students are working through lunch and on the bus,” said Schuler. “I see students break down.”

Wren also said she has seen the toll of AP on students.

“What I’m really seeing in classes that are really struggling that is breaking my heart is the embarrassment,” said Wren. They’re embarrassed that they’re not doing well and need help. That’s how students feel; they feel angry, frustrated.”

The common piece of advice from some AP teachers has been for each student to take the classes that are right for him or her.

“I think they need to be strategic. What is going to be the purpose of taking the AP; is it for status, college credit, enjoyment?” said Schuler.

“I think they need to know how much is too much,” he said. There is this thing called high school, and you’re only here for four years. And at some point, you guys have to have a high school life.”

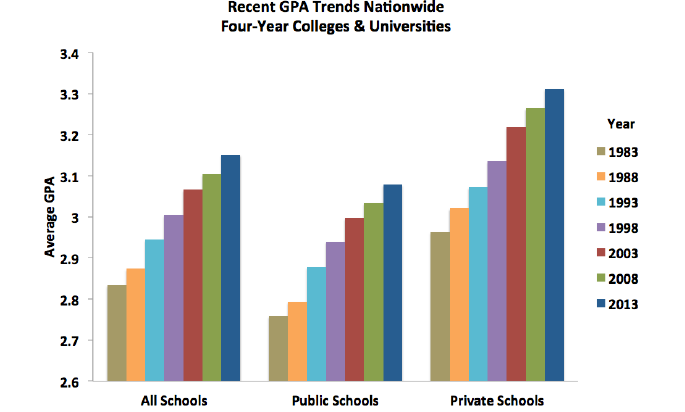

Part 6: Grade Inflation

Graph published by Stuart Rojstaczer, a former Duke University professor who now conducts private research on international grade inflation. He is a critic of modern academia, and has been featured on the New York Times and NPR.

The U.S Department of Education reported that the average GPA in 1990 for high school graduates was a 2.68. In 2009, it reported that the number had risen to a 3.0.

This could be the result of education reform bills and a general increase in the quality of education across the United States. It could also be the result of grade inflation.

Grade inflation can be defined as the idea that GPA and other academic scores have increased artificially, rather than legitimately. It has been studied by university professors, and teachers interviewed said it is noticeable at the high school level.

Some teachers condemn this trend as a fault in American education that contributes to student anxiety.

“Grade Inflation: a Crisis in College Education,” a 2003 book by Texas A&M statistics professor Valen Johnson, describes how officials at a different school, Dartmouth College, noticed that its average GPA increased from 3.06 in 1968 to 3.23 in 1994.

The school did not celebrate. Instead, it enacted a policy to fix what is believed to be grade inflation.

Dartmouth began compiling median scores for each course, with the intention of alerting teachers to upward trends that could signal grade inflation. The effect was that grade inflation at Dartmouth shrank significantly.

Some teachers at Cambridge said grade inflation is observable here, too.

“I see teachers giving the easy A more and more,” said English teacher Suzanne Wren.

Wren said she believes grade inflation has become more widespread as the burden of grades has shifted away from students and onto teachers.

Her reasoning is that legislation like 2001’s No Child Left Behind Act results in many teachers passing students who ought to fail. The legislation includes measures that can punish teachers who fail students, said Wren.

This, she explained, is the root of grade inflation.

“I see it more in younger students,” Wren explained. She said students get to her class and say “they’ve never had anything below an A” in an English class.

She said she sees students, especially in her honors classes, who are “crazed” after receiving grades lower than As. In her view, grade inflation is among the factors that contribute to students’ academic anxiety.

STEM Director Ellen Kerr, who teaches AP Chemistry, said that when prerequisite classes to AP courses are taught less rigorously, it can affect the ability of students to meet the rigor of AP courses.

Students interviewed said they were not knowledgeable on the subject of grade inflation.

“I know about it. I’m not confident enough to talk about it,” said senior Payton Faw.

Counseling department head Samiah Garcia has her own theory on what drives grade inflation at the high school level. It begins with students’ obsession with GPA ranks.

“Grades are driven by ranks. Grades get inflated by the extra seven points,” said Garcia.

Garcia explained that this makes students more inclined to take rigorous courses, which ultimately waters down the curriculum. Garcia explained that more students are taking difficult courses, such as honors or AP. When some of these students aren’t prepared, teachers sometimes compensate by inflating grades.

The school, as of the 2017-2018 academic year, will cease to use ranks according to Garcia.

Garcia also explained how the recession of the late 2000s has contributed to grade inflation. She said the recession discouraged many families from sending their children to prestigious, and expensive, universities, even though they qualified for admission to these schools.

Instead, these students have stayed in state, where they can obtain the HOPE scholarship, making it more competitive.

This trend has continued to today, she explained.

“A long time ago, if you wanted to go to college, you went,” said Wren.

The spike in admissions qualifications, particularly in the case of GPA, has led to pressure on educators to buff grades, according to Garcia. In other words, the GPA has risen only partially because of improved learning among students.

The effects of potentially inflated GPAs, Garcia said, may present themselves in the form of poorer curriculum and an increase in student anxiety.

“I think there’s a lot of pressure on students to achieve,” said Kerr. “Not all students need to be in college courses when they’re in high school.”